SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY IN ANCIENT INDIA

• Mathematics has been called by the general name of Ganita which includes Arithmetics, Geometry, Algebra, Astronomy and Astrology.

o Arithmetic is called by several names such as Pattin Ganita (calculations on board), Anka Ganita (calculations with numerals).

o Geometry is called Rekha Ganita (line works) and Algebra, Bija Ganita (seed analysis).

o Astronomy and Astrology are included in the term Jyotisa.

• India has a rich heritage of science and technology. The dependence on nature could be overcome by developments in science. In ancient India, religion and science worked in close proximity. Let us find out about the developments in the different branches of science in the ancient period.

Astronomy

• Astronomy made great progress. The movement of planets came to be emphasized and closely observed.

• Jyotishvedanga texts established systematic categories in astronomy but the more basic problem was handled by Aryabhatta (499 AD). His Aryabhattiya is a concise text containing 121 verses. It contains separate sections on astronomical definitions, methods of determining the true position of the planets, description of the movement of the sun and the moon and the calculation of the eclipses.

• The reason he gave for eclipse was that the earth was a sphere and rotated on its axis and when the shadow of the earth fell on the moon, it caused Lunar eclipse and when the shadow of the moon fell on the earth, it caused Solar eclipse. On the contrary, the orthodox theory explained it as a process where the demon swallowed the planet.

• All these observations have been described by Varahamihira in Panch Siddhantika which gives the summary of five schools of astronomy present in his time. Aryabhatta deviated from Vedic astronomy and gave it a scientific outlook which became a guideline for later astronomers.

• Astrology and horoscope were studied in ancient India. Aryabhatta’s theories showed a distinct departure from astrology which stressed more on beliefs than scientific explorations.

Mathematics

• The town planning of Harappa shows that the people possessed a good knowledge of measurement and geometry. By third century AD mathematics developed as a separate stream of study.

• Indian mathematics is supposed to have originated from the Sulvasutras. Apastamba in second century BC, introduced practical geometry involving acute angle, obtuse angle and right angle. This knowledge helped in the construction of fire altars where the kings offered sacrifices.

• The three main contributions in the field of mathematics were the notation system, the decimal system and the use of zero. The notations and the numerals were carried to the West by the Arabs. These numerals replaced the Roman numerals.

• Zero was discovered in India in the second century BC. Brahmagupta’s Brahmasputa Siddhanta is the very first book that mentioned ‘zero’ as a number, hence, Brahmagupta is considered as the man who found zero. He gave rules of using zero with other numbers.

• Aryabhatta discovered algebra and also formulated the area of a triangle, which led to the origin of Trignometry.

• The Surya Siddhanta is a very famous work. Varahamihira’s Brihatsamhita of the sixth century AD is another pioneering work in the field of astronomy. His observation that the moon rotated around the earth and the earth rotated around the sun found recognition and later discoveries were based on this assertion.

• Mathematics and astronomy together ignited interest in time and cosmology. These discoveries in astronomy and mathematics became the cornerstones for further research and progress.

Medicine

• Diseases, cure and medicines were mentioned for the first time in the Atharva Veda. Fever, cough, consumption, diarrhoea, dropsy, sores, leprosy and seizure are the diseases mentioned. The diseases are said to be caused by the demons and spirits entering one’s body. The remedies recommended were replete with magical charms and spells.

• From 600 BC began the period of rational sciences. Takshila and Taranasi emerged as centres of medicine and learning.

• The two important texts in this field are Charaksamhita by Charak and Sushrutsamhita by Sushruta. How important was their work can be understood from the knowledge that it reached as far as China, Central Asia through translations in various languages.

• Surgery came to be mentioned as a separate stream around fourth century AD. Sushruta was a pioneer of this discipline. He considered surgery as “the highest division of the healing arts and least liable to fallacy”.

• He mentions 121 surgical instruments. Along with this he also mentions the methods of operations, bone setting, cataract and so on. The surgeons in ancient India were familiar with plastic surgery (repair of noses, ears and lips).

• Sushruta mentions 760 plants. All parts of the plant roots, barks, flowers, leaves etc. were used. Stress was laid on diet (e.g. salt free diet for nephrites). Both the Charaksamhita and the Sushrutsamhita became the predecessors of the development of Indian medicine in the later centuries.

• However, surgery suffered in the early medieval time since the act of disecting with a

Metallurgy

• The glazed potteries and bronze and copper artefacts found in the Indus valley excavations point towards a highly developed metallurgy. The Vedic people were aware of fermenting grain and fruits, tanning leather and the process of dyeing.

• By the first century AD, mass production of metals like iron, copper, silver, gold and of alloys like brass and bronze were taking place. The iron pillar in the Qutub Minar complex is indicative of the high quality of alloying that was being done.

• Alkali and acids were produced and utilised for making medicines. This technology was also used for other crafts like producing dyes and colours. Textile dyeing was popular.

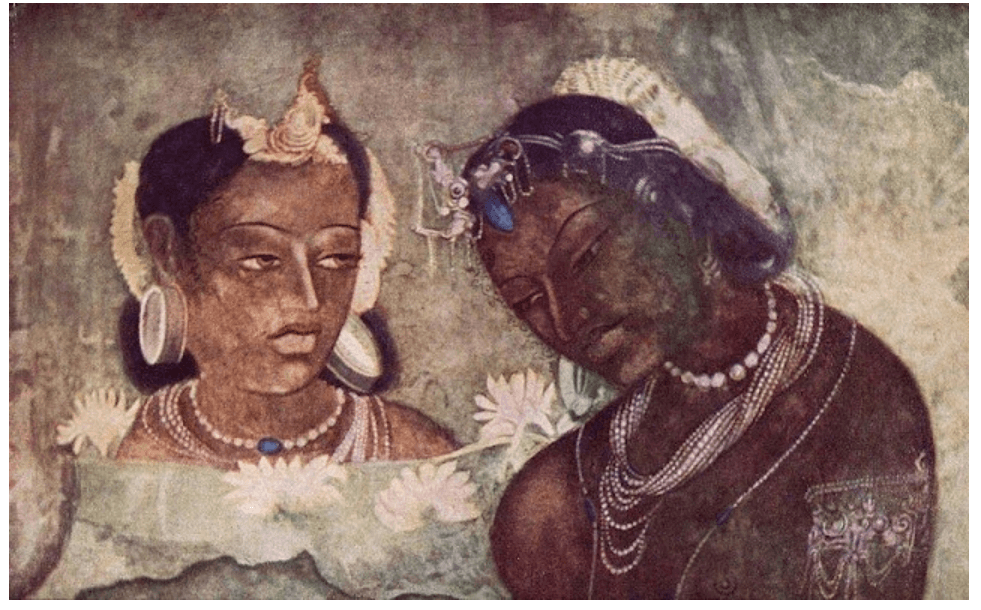

• The Ajanta frescoes reflect on the quality of colour. These paintings have survived till date.

• A two metre high bronze image of Buddha has been discovered at Sultanganj (near Bhagalpur) in Bihar.

Geography

• The constant interaction between man and nature forced people to study geography. Though the people were clear about their own physical geography, that of China and also the Western countries, they were unaware of their position on the earth and the distances with other countries.

• Indians also contributed to shipbuilding. In the ancient period, voyages and navigation was not a familiar foray for the Indians. However, Lothal, a site in Gujarat has the remains of a dockyard proving that trade flourished in those days by sea.

• In the early medieval period with the development of the concept of tirtha and tirtha yatra, a vast mass of geographical information was accumulated. They were finally compiled as parts of Puranas. In many cases, separate sthala purana was also compiled.

SCIENTISTS OF ANCIENT INDIA

MATHEMATICS & ASTRONOMY

• Science and Mathematics were highly developed during the ancient period in India. Ancient Indians contributed immensely to the knowledge in Mathematics as well as various branches of Science.

• Even though many theories of modern day mathematics were actually known to ancient Indians, however, since ancient Indian mathematicians were not as good in documentation and dissemination as their counterparts in the modern western world, their contributions did not find the place they deserved.

• Moreover, the western world ruled over most of the world for a long time, which empowered them to claim superiority in every way, including in the field of knowledge.

Baudhayan

• Baudhayan was the first one ever to arrive at several concepts in Mathematics, which were later rediscovered by the western world.

• The value of pi was first calculated by him. The value of pi is useful in calculating the area and circumference of a circle. What is known as Pythagoras theorem today is already found in Baudhayan’s Sulva Sutra, which was written several years before the age of Pythagoras.

Aryabhatta

• Aryabhatta was a fifth century mathematician, astronomer, astrologer and physicist. He was a pioneer in the field of mathematics.

• At the age of 23, he wrote Aryabhattiya, which is a summary of mathematics of his time. There are four sections in this scholarly work.

• In the first section he describes the method of denoting big decimal numbers by alphabets. In the second section, we find difficult questions from topics of modern day Mathematics such as number theory, geometry, trigonometry and Beejganita (algebra).

• The remaining two sections are on astronomy. Aryabhatta showed that zero was not a numeral only but also a symbol and a concept.

• Discovery of zero enabled Aryabhatta to find out the exact distance between the earth and the moon. The discovery of zero also opened up a new dimension of negative numerals.

• In ancient India, the science of astronomy was well advanced. It was called Khagolshastra. Khagol was the famous astronomical observatory at Nalanda, where Aryabhatta studied.

• The aim behind the development of the science of astronomy was the need to have accurate calendars, a better understanding of climate and rainfall patterns for timely sowing and choice of crops, fixing the dates of seasons and festivals, navigation, calculation of time and casting of horoscopes for use in astrology. Knowledge of astronomy, particularly knowledge of the tides and the stars, was of great importance in trade, because of the requirement of crossing the oceans and deserts during night time.

• Disregarding the popular view that our planet earth is ‘Achala’ (immovable), Aryabhatta stated his theory that ‘earth is round and rotates on its own axis’.

• He explained that the appearance of the sun moving from east to west is false by giving examples. One such example was: When a person travels in a boat, the trees on the shore appear to move in the opposite direction.

• He also correctly stated that the moon and the planets shined by reflected sunlight. He also gave a scientific explanation for solar and lunar eclipse clarifying that the eclipse were not because of Rahhu and/or Ketu or some other rakshasa (demon,).

Brahmgupta

• In 7th century, Brahmgupta took mathematics to heights far beyond others. In his methods of multiplication, he used place value in almost the same way as it is used today.

• He introduced negative numbers and operations on zero into mathematics. He wrote Brahm Sputa Siddantika through which the Arabs came to know our mathematical system.

Bhaskaracharya

• Bhaskaracharya was the leading light of 12th Century. He was born at Bijapur, Karnataka.He is famous for his book Siddanta Shiromani.

• It is divided into four sections: Lilavati (Arithmetic), Beejaganit (Algebra), Goladhyaya (Sphere) and Grahaganit (mathematics of planets).

• Bhaskara introduced Chakrawat Method or the Cyclic Method to solve algebraic equations. This method was rediscovered six centuries later by European mathematicians, who called it inverse cycle.

• In the nineteenth century, an Englishman, James Taylor, translated Lilavati and made this great work known to the world.

Mahaviracharya

• There is an elaborate description of mathematics in Jain literature (500 B.C -100 B.C).

• Jain gurus knew how to solve quadratic equations. They have also described fractions, algebraic equations, series, set theory, logarithms and exponents in a very interesting manner.

• Jain Guru Mahaviracharya wrote Ganit Sara Sangraha in 850A.D., which is the first textbook on arithmetic in present day form. The current method of solving Least common Multiple (LCM) of given numbers was also described by him.

SCIENCE

• As in Mathematics, ancient Indians contributed to the knowledge in Science, too.

Kanad

• Kanad was a sixth century scientist of Vaisheshika School, one of the six systems of Indian philosophy. His original name was Aulukya. He got the name Kanad, because even as a child, he was interested in very minute particles called “kana”.

• His atomic theory can be a match to any modern atomic theory. According to Kanad, material universe is made up of kanas (anu/atom) which cannot be seen through any human organ.

• These cannot be further subdivided. Thus, they are indivisible and indestructible.

Varahamihira

• Varahamihira was another well known scientist of the ancient period in India. He lived in the Gupta period. Varahamihira made great contributions in the fields of hydrology, geology and ecology.

• He was one of the first scientists to claim that termites and plants could be the indicators of the presence of underground water. He gave a list of six animals and thirty plants, which could indicate the presence of water.

• He gave very important information regarding termites (Deemak or insects that destroy wood), that they go very deep to the surface of water level to bring water to keep their houses (bambis) wet.

• Another theory, which has attracted the world of science is the earthquake cloud theory given by Varahmihira in his Brhat Samhita. The thirty second chapter of this samhita is devoted to signs of earthquakes. He has tried to relate earthquakes to the influence of planets, undersea activities, underground water, unusual cloud formation and abnormal behaviour of animals.

• Another field where Varahamihira’s contribution is worth mentioning is Jyotish or Astrology. Jyotish, which means science of light, originated with the Vedas. It was presented scientifically in a systematic form by Aryabhatta and Varahmihira.

• Aryabhatta devoted two out of the four sections of his work Aryabhattiya to astronomy, which is the basis for Astrology.

• Varahamihira was one of the nine gems, who were scholars, in the court of Vikramaditya. Varahamihira’s predictions were so accurate that king Vikramaditya gave him the title of ‘Varaha’.

Nagarjuna

• Nagarjuna was a tenth century scientist. The main aim of his experiments was to transform base elements into gold, like the alchemists in the western world.

• Even though he was not successful in his goal, he succeeded in making an element with gold-like shine. Till date, this technology is used in making imitation jewelry.

• In his treatise, Rasaratnakara, he has discussed methods for the extraction of metals like gold, silver, tin and copper.

MEDICINE

• Scientific knowledge was in a highly advanced stage in ancient India. In keeping with the times, Medical Science was also highly developed.

• Ayurveda is the indigenous system of medicine that was developed in Ancient India. The word Ayurveda literally means the science of good health and longevity of life. This ancient Indian system of medicine not only helps in treatment of diseases but also in finding the causes and symptoms of diseases. It is a guide for the healthy as well as the sick.

• It defines health as an equilibrium in three doshas, and diseases as disturbance in these three doshas. While treating a disease with the help of herbal medicines, it aims at removing the cause of disease by striking at the roots.

• A treatise on Ayurveda, Atreya Samhita, is the oldest medical book of the world.

• Charak is called the father of ayurvedic medicine and Susruta the father of surgery. Susruta, Charak, Madhava, Vagbhatta and Jeevak were noted ayurvedic practitioners.

Susruta

• Susruta was a pioneer in the field of surgery. He considered surgery as “the highest division of the healing arts and least liable to fallacy”. He studied human anatomy with the help of a dead body.

• In Susruta Samhita, over 1100 diseases are mentioned including fevers of twenty-six kinds, jaundice of eight kinds and urinary complaints of twenty kinds. Over 760 plants are described. All parts, roots, bark, juice, resin, flowers etc. were used. Cinnamon, sesame, peppers, cardamom, ginger are household remedies even today.

• In Susruta Samhita, the method of selecting and preserving a dead body for the purpose of its detailed study has also been described. The dead body of an old man or a person who died of a severe disease was generally not considered for studies. The body needed to be perfectly cleaned and then preserved in the bark of a tree.

• It was then kept in a cage and hidden carefully in a spot in the river. There the current of the river softened it. After seven days it was removed from the river. It was then cleaned with a brush made of grass roots, hair and bamboo. When this was done, every inner or outer part of the body could be seen clearly.

• Susruta’s greatest contribution was in the fields of Rhinoplasty (plastic surgery) and Ophthalmic surgery (removal of cataracts). In those days, cutting of nose and/or ears was a common punishment. Restoration of these or limbs lost in wars was a great blessing. In Susruta Samhita, there is a very accurate step-by-step description of these operations.

• Surprisingly, the steps followed by Susruta are strikingly similar to those followed by modern surgeons while doing plastic surgery. Susruta Samhita also gives a description of 101 instruments used in surgery. Some serious operations performed included taking foetus out of the womb, repairing the damaged rectum, removing stone from the bladder, etc.

Charak

• Charak is considered the father of ancient Indian science of medicine. He was the Raj Vaidya (royal doctor) in the court of Kanishka. His Charak Samhita is a remarkable book on medicine.

• It has the description of a large number of diseases and gives methods of identifying their causes as well as the method of their treatment. He was the first to talk about digestion, metabolism and immunity as important for health and so medical science.

• In Charak Samhita, more stress has been laid on removing the cause of disease rather than simply treating the illness. Charak also knew the fundamentals of Genetics.

Yoga & Patanjali

• The science of Yoga was developed in ancient India as an allied science of Ayurveda for healing without medicine at the physical and mental level.

• The term Yoga has been derived from the Sanskrit work Yoktra. Its literal meaning is “yoking the mind to the inner self after detaching it from the outer subjects of senses”. Like all other sciences, it has its roots in the Vedas.

• It defines chitta i.e. dissolving thoughts, emotions and desires of a person’s consciousness and achieving a state of equilibrium. It sets in to motion the force that purifies and uplifts the consciousness to divine realization. Yoga is physical as well as mental.

• Physical yoga is called Hathyoga. Generally, it aims at removing a disease and restoring healthy condition to the body. Rajayoga is mental yoga. Its goal is self realization and liberation from bondage by achieving physical mental, emotional and spritiual balance.

• Yoga was passed on by word of mouth from one sage to another. The credit of systematically presenting this great science goes to Patanjali. In the Yoga Sutras of Patanjali, Aum is spoken of as the symbol of God. He refers to Aum as a cosmic sound, continuously flowing through the ether, fully known only to the illuminated.

• Besides Yoga Sutras, Patanjali also wrote a work on medicine and worked on Panini’s grammar known as Mahabhasaya.

SCIENTIFIC AND TECHNOLOGICAL DEVELOPMENTS IN MEDIEVAL INDIA

• During the medieval period (eleventh to eighteenth century) science and technology in India developed along two lines: one concerned with the already charted course of earlier traditions and the other with the new influences which came up as a result of Islamic and European influence.

• The maktabs and madrasas came into existence that followed a set curricular. These institutions used to receive royal patronage. Learned men from Arabia, Persia and Central Asia were invited to teach in these madrasas.

• A large number of karkhana (workshops) were maintained by the kings and the nobles to supply provisions, stores and equipment to royal household and government departments.

• The karkhanas not only worked as manufacturing agencies but also served as centres for technical and vocational training to young men. The karkhanas trained and turned out artisans and craftsmen in different branches, who later set up their own independent karkhanas (workshops).

• Muslim rulers attempted to reform the curriculum of primary schools. Some important subjects like arithmetic, mensuration, geometry, astronomy, accountancy, public administration and agriculture were included in the course of studies for primary education.

• Though special efforts were made by the rulers to carry out reforms in education, yet science did not make much headway during this period. Efforts were made to seek a kind of synthesis between the Indian traditional scientific culture and the prevalent approach to science in other countries.

Biology

• Hamsadeva compiled Mrga-pasi-sastra in the thirteenth century which gives a general, though not always scientific account of some of the beasts and birds of hunting.

• The medieval rulers, as warriors and hunters, kept animals such as horses, dogs, cheetahs and falcons. Animals, both domesticated and wild, existed in their menageries.

• Akbar showed special interest in producing good breeds of domestic animals, elephants and horses.

• Jahangir, in his Tuzuk-i-Jahangiri, recorded his observations and experiments of weeding and hybridisation. He described about thirty-six species of animals.

• His court artists, specially Mansur, produced elegant and accurate portraiture of animals, some of which are still preserved in several museums and private collections.

• As a naturalist, Jahangir was interested in the study of plants and his court artists in their floral portraiture describe some fifty-seven plants.

Mathematics

• Brahmagupta the great 7th century mathematician has given a description of negative numbers as debts and positive numbers as fortunes, which shows that ancient Indians knew the utility of mathematics for practical trade.

• In the early medieval period the two outstanding works in mathematics were Ganitasara by Sridhara and Lilavati by Bhaskara.

• Ganitasara deals with multiplication, division, numbers, cubes, square roots, mensuration and so on.

• Ganesh Daivajna produced Buddhivilasini, a commentary on Lilavati, containing a number of illustrations. In 1587, Lilavati was translated into Persian by Faidi.

• Bija Ganita was translated by Ataullah Rashidi during Shah Jahan’s reign. Nilkantha Jyotirvid, a courtier of Akbar, compiled Tajik, introducing a large number of Persian technical terms.

• Akbar ordered the introduction of mathematics as a subject of study, among others in the educational system. Nasiruddin Tusi, the founder director of the Maragha observatory, was recognised as an authority.

Chemistry

• Before the introduction of writing paper, ancient literature was preserved generally on palm leaves in South India and birch-bark (bhoj-patra) in Kashmir and other northern regions of the country.

• Use of paper began during the Medieval period. Kashmir, Sialkot, Zafarabad, Patna, Murshidabad, Ahmedabad, Aurangabad, Mysore were well-known centres of paper production. During Tipu’s time, Mysore possessed a paper-making factory, producing a special type of paper that had a gold surface.

• The Mughals knew the technique of production of gunpowder and its use in guns. Indian craftsmen learnt the technique and evolved suitable explosive compositions. They were aware of the method of preparation of gunpowder using saltpetre, sulphur and charcoal in different ratios for use in different types of guns.

• Tuzuk-i-Baburi gives an account of the casting of cannons. The melted metal was made to run into the mould till full and then cooled down.

• Besides explosives, other items were also produced. Ain-i-Akbari speaks of the ‘Regulations of the Perfume Office of Akbar’. The attar of roses was a popular perfume, the discovery of which is attributed to the mother of Nurjehan. Mention may also be made here of the glazed tiles and pottery during the period.

Astronomy

• In astronomy, a number of commentaries dealing with the already established astronomical notions appeared. Ujjain, Varanasi, Mathura and Delhi were the main observatories.

o Firoz Shah Tughaq established observation posts at Delhi.

o Firoz Shah Bahmani, under Hakim Hussain Gilani and Syed Muhammad Kazimi, set up an observatory in Daulatabad. Both lunar and solar calendars were in use.

o Mahendra Suri, a court astronomer of Firoz Shah developed an astronomical instrument called Yantraja.

o Nilakantha Somasutvan produced a commentary on Aryabhatta. Kamalakar studied the Islamic ideas on astronomy. He was an authority on Islamic knowledge as well.

o Jaipur Maharaja, Sawai Jai Singh II set five astronomical observatories (Jantar-Mantar) in Delhi, Ujjain, Varanasi, Mathura and Jaipur.

Medicine

• There was an attempt to develop specialised treatises on different diseases. Pulse and urine examinations were conducted for diagnostic purposes.

• The Sarangdhara Samhita recommends use of opium for medicines. The rasachikitsa system, dealt principally with a host of mineral medicines including metallic preparations.

• The Tuhfat-ul-Muminin was a Persian treatise written by Muhammad Munin in seventeenth century which discusses the opinions of physicians.

• The Unani Tibb is an important system of medicine which flourished in India in the medieval period. The Unani medicine system came to India along with the Muslims around the eleventh century and soon found a congenial environment for its growth.

• Ali-bin-Rabban summarized the whole system of Greek medicine as well as the Indian medical knowledge in the book Firdausu-Hikmat.

• Firoz Shah Tughlaq wrote a book, Tibbe Firozshahi. The Tibbi Aurangzebi, dedicated to Aurangzeb, is based on Ayurvedic sources.

Agriculture

• In the medieval period, the pattern of agricultural practices was more or less the same as that in early and early ancient India. Some important changes, however, were brought about by the foreigners such as the introduction of new crops, trees and horticultural plants. The principal crops were wheat, rice, barley, millets, pulses, oilseeds, cotton, sugarcane and indigo.

o The Western Ghats continued to yield black pepper of good quality and Kashmir maintained its tradition for saffron and fruits.

o Ginger and cinnamon from Tamilnadu, cardamom, sandalwood and coconuts from Kerala were becoming increasingly popular.

o Tobacco, chillies, potato, guava, custard apple, cashew and pineapple were the important new plants which made India their home in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries.

o The region of Malwa and Bihar were also well known for the production of opium from the poppy plants. Improved horticultural methods were adopted with great success.

• The systematic mango grafting was introduced by the Jesuits of Goa in the middle of sixteenth century.

• In the field of irrigation, wells, tanks, canals, rahats, charas (bucket made of leather) and dhenkli, were used to lift water with the help of yoked oxen, which continued to be the means of irrigation. Persian wheel was used in and around Agra region. In the medieval period, agriculture was placed on a solid foundation by the State which brought about a system of land measurement and land classification, beneficial both to the rulers and to the tillers.

SCIENTISTS IN MEDIEVAL PERIOD

• The medieval period marks the coming of Muslims in India. By this time, the traditional indigenous classical learning had already received a setback. The pattern of education as prevalent in Arab countries was gradually adopted during this period.

• As a result, Maktabs and Madrasas came into existence. These institutions used to receive royal patronage. A chain of madrasas, opened at several places, followed a set curriculum.

• Apart from the talent available locally in the country, learned men from Arabia, Persia and Central Asia were also invited to take charge of education in madrasas.

• Many Muslim rulers attempted to reform the curriculum of primary schools. Some important subjects like Arithmetic, Mensuration, Geometry, Astronomy, Accountancy, Public Administration and Agriculture were included in the courses of studies for primary education. Though special efforts were made by the ruler to carry out reforms in education, yet sciences did not make much headway.

• Large workshops called karkhanas were maintained to supply provision, stores and equipments to royal household and government departments. The karkhanas not only worked as manufacturing agencies, but also served as centres for technical and vocational training to young people

Mathematics

• Several works in the field of Mathematics were produced during this period. Narayana Pandit, son of Narsimha Daivajna was well known for his works in Mathematics – Ganitakaumudi and Bijaganitavatamsa.

• Gangadhara, in Gujarat, wrote Lilavati Karamdipika, Suddhantadipika , and Lilavati Vyakhya. These were famous treatises which gave rules for trigonometrical terms like sine, cosine tangent and cotangent.

• Faizi, at the behest of Akbar, translated Bhaskara’s Bijaganit. Akbar ordered to make Mathematics as a subject of study, among others in the education system.

Biology

• Similarly, there were advancements in the field of Biology. Both Babur and Akbar, in spite of being busy in their political preoccupations and war, found time to study the work of naturalists and biologists.

• Akbar had a special interest in producing good breeds of domestic animals like elephants and horses. Jahangir, in his work, Tuzuk-i-jahangiri – recorded his observations and experiments on breeding and hybridization.

• His court artists, specially, Mansur, produced elegant and accurate portraitures of animals. Some of these are still preserved in several museums and private collections.

Chemistry

• In the medieval period, use of paper had begun. An important application of chemistry was in the production of paper. Kashmir, Sialkot, Zafarabad, Patna, Murshidabad, Ahmedabad, Aurangabad and Mysore became well known centres of paper production. The paper making technique was more or less the same throughout the country differing only in preparation of the pulp from different raw materials.

• The Mughals knew the technique of production of gunpowder and its use in gunnery, another application of chemistry. The work Sukraniti attributed to Sukracharya contains a description of how gunpowder can be prepared using saltpetre, sulphur and charcoal in different ratios for use in different types of guns..

• The work Ain-i-Akbari also speaks of the regulation of the perfume office of Akbar.

Astronomy

• Astronomy was another field that flourished during this period. In astronomy, a number of commentaries dealing with the already established astronomical notions appeared.

• Mahendra Suri, a court astronomer of Emperor Firoz Shah, developed an astronomical, instrument ‘Yantraja’. Paramesvara and Mahabhaskariya, both in Kerala, were famous families of astronomers and almanac-makers.

• Kamalakar studied the Islamic astronomical ideas. He was an authority on Islamic knowledge.

Medicine

• The Ayurveda system of medicine did not progress as vigorously as it did in the ancient period because of lack of royal patronage. However, some important treatises on Ayurveda like the Sarangdhara Samhita and Chikitsasamgraha by Vangasena were compiled.

• The Sarangdhara Samhita, written in the thirteenth century, includes use of opium in its material medica and urine examination for diagnostic purpose. The drugs mentioned include metallic preparation of the rasachikitsa system and even imported drugs.

• The Rasachikitsa system, dealt principally with a host of mineral medicines, both mercurial and non-mercurial. The Siddha system mostly prevalent in Tamil Nadu was attributed to the reputed Siddhas, who were supposed to have evolved many life-prolonging compositions, rich in mineral medicines.

Agriculture

• Imperial Mughal Gardens were suitable areas where extensive cultivation of fruit trees came up.

• For irrigation, wells, tanks, canals, rahat, charas and dhenkli charas (a sort of a bucket made of leather used to lift water with the help of yoked oxen) were used. Persian wheel was used in the Agra region.

• In the medieval period, agriculture was placed on a solid foundation by the State by introducing a system of land measurement and land classification, beneficial both to the rulers as well as the tillers.

INDIAN PAINTINGS

Shadang in Indian painting

Around 1st century BC, six limbs of Indian Painting, were evolved, laying down the main principles of the art.

Shadang or the six limbs of Indian art find their first mention in Vatsyayana’s Kama Sutra around 3rd century AD.

Vishnudharmottara Purana (700 A.D.) contains Chitrasutra which describes the six organs of painting. The six different limbs were actually six different points or strokes which were emphasized to infuse more life to the paintings.

These ‘Six Limbs’ have been translated as follows:

1. Rupabheda (secrets of form)

Knowledge of appearances viz. facial expressions & features

2. Pramanam (Proportion)

Correct perception, measure and structure

3. Bhava (Emotional Disposition)

Portraying feelings on canvas

4. Lavanya Yojanam (Gracefulness in composition)

Portrays Grace & Poise

5. Sadrisyam (Similitude)

Defines similarities between the real & the creation

6. Varnika Bhanga (Colour differentiation)

Artistic manner of using the right brush and colours, invented by Rabindranath Tagore

The subsequent development of painting by the Buddhists indicates that these ‘ Six Limbs ‘ were put into practice by Indian artists, and are the basic principles on which their art was founded.

Important Source of Information for Paintings

Mudrarakshasa – Sanskrit play was written by Vishakhadutta – mentions many types of Paintings during the 4th century period.

Brahmanical Literature – the reference to the art of paintings with the representation of myths

Buddhist Literature – mentions different styles of paintings with various base and themes.

Vinaya Pitaka – 3rd – 4th century BC – houses containing paintings

Prehistoric Cave Paintings

The pre-historic paintings are generally executed in rocks in the caves.

The major themes are Animals like elephant, rhinoceros, cattle, snake, deer, etc.. and other natural elements like plants.

The pre-historic paintings are categorised into three phases – Paleolithic, Mesolithic and Chalcolithic.

Characteristics

Used minerals for pigments Eg: ochre or geru. They used minerals in different colours.

Major Themes: group hunting, grazing, riding scenes, etc..

The colours and size of the paintings have been evolved through the ages.

Examples: Bhimbetka caves, MP; Jogimara caves, Chattisgarh; Narsingarh, MP

Genres of Indian Painting

Indian paintings can be broadly classified as murals and miniatures.

Murals are large works executed on the walls of solid structures directly, as in the Ajanta Caves & Kailash temple (Ellora)

Miniature paintings are executed on a very small scale for books or albums on perishable material such as paper and cloth.

Mural Paintings

Mural is inherently different from all other forms of pictorial art & is organically connected with architecture.

Mural is the only form of painting that is truly three-dimensional, since it modifies and partakes of a given space.

Mural paintings are applied on dry wall with the major use of egg, yolk, oil, etc.

A mural artist must conceive pictorially a theme on the appropriate scale with reference to the structural exigencies of the wall & to the idea expressed.

The history of Indian murals starts in ancient & early medieval times, from 2nd century BC to 8th – 10th century AD.

Notable examples → Ajanta Caves, Bagh Caves, Sittanavasal Caves, Armamalai Cave (Tamil Nadu), Kailasa temple (Ellora Caves)

Murals from this period depict mainly religious themes of Buddhism, Jainism and Hinduism

Fresco Paintings

A technique of mural painting executed upon freshly laid lime plaster

Water is used as the vehicle for the pigment

With the setting of the plaster; the painting becomes an integral part of the wall.

Ajanta Murals Paintings

Depict a large number of incidents from the life of the Buddha (Jataka Tales)

Exclusively Buddhist, excepting decorative patterns on the ceilings and the pillars.

Prominent feature → Half closed drooping eyes

Ellora Murals Paintings

Painted in rectangular panels with thick borders with following

Prominent features → Sharp twist of the head + painted angular bents of the arms + sharp projected nose + long drawn open eyes + concave curve of the close limbs

Badami Mural Paintings

A cave site in Karnataka, patronized by Chalukya king, Manglesha

Depictions in the caves show Vaishnava affiliation, Therefore, the cave is popularly known as Vishnu cave.

Only a fragment of painting has survived on the vaulted roof of the front mandapa

Badami cave painting represents an extension of the tradition of mural painting from Ajanta to Badami in south India

It is noteworthy to observe that the contours of different parts of the face of the face create protruding structures of face

Bagh Caves, Madhya Pradesh

Tightly modelled and stronger outline

More earthly and human

Mostly secular in nature

Ravan Chhaya, Odisha

7th century AD

Fresco Paintings

Murals under the Pallava, Pandava and Cholas

Paintings at the Kanchipuram temple were patronised by Pallava king, Rajsimha

Paintings at Tirumalaipuram caves & Jaina caves at Sittanvasal were patronised by Padayas

Paintings at Nartamalai & Brihadeswara temple were patronized by Cholas

Sittanavasal Cave paintings, Tamil Nadu

Around the 9th and 10th century

Not only on walls but also on pillars and ceilings

Mostly paintings in Jain temples

Prominent feature of Cholas art → wide open eyes

Notable Cholas art example → Dancing girl from Brihadeshwara temple of Tanjore

Vijayanagara murals (13th century)

Paintings at Virupaksha temple (Hamphi) & Lepakshi temple (Andhra Pradesh) were patronised by Vijayanagara Kings

Lepakshi, Karnataka

Mostly in temple walls

Vijayanagara period

Religious and secular themes

Miniature Paintings

The Palas of Bengal were the pioneers of miniature painting in India.

The art of miniature painting reached its glory during the Mughal period.

The tradition of miniature paintings was carried forward by the painters of different Rajasthani schools of painting like the Bundi, Kishangarh, Jaipur, Marwar & Mewar.

The Ragamala paintings also belong to this school, as does the Company painting produced for British clients under the British Raj.

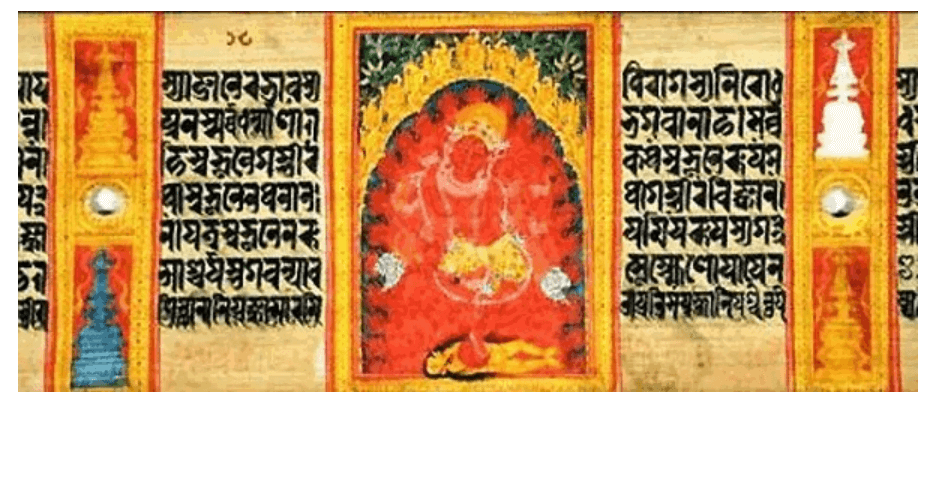

The Pala School (11th – 12th century)

Earliest examples of miniature painting in India

Exist in the form of illustrations to the religious texts on Buddhism executed under the Palas of the eastern India & the Jain texts executed in western India

The Buddhist monasteries of Nalanda, Odantapuri, Vikramsila & Somarupa were great centers of Buddhist learning and art.

A large number of manuscripts on palm-leaf relating to the Buddhist themes were written, illustrated with the images of Buddhist deities at these centers

The Pala painting is characterized by sinuous line and subdued tones of colour

Pala paintings resemble the ideal forms of contemporary bronze and stone sculpture

Represents a naturalistic style which reflects a feeling of the classical Ajanta art

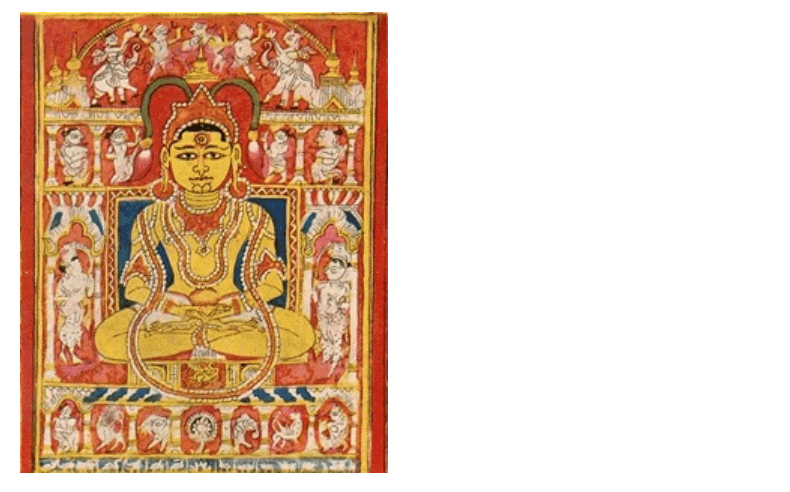

Western Indian School of Painting

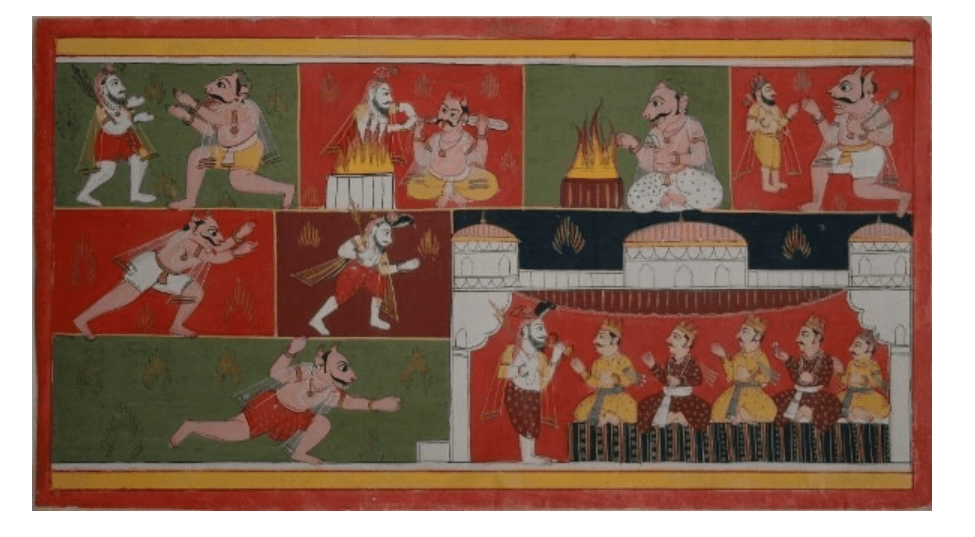

Also called Jaina Painting, largely devoted to the illustration of Jaina religious texts of the 12th–16th century

Notable sites → Gujrat, Uttar Pradesh, Central India & Orissa

Characterized by simple, bright colours, highly conventionalized figures, and wiry, angular drawing

The naturalism of early Indian wall painting is entirely absent.

The earliest manuscripts are on palm leaves with the figures shown from a frontal view

The facial type, with its pointed nose, resembles to wall paintings at Ellora

Prominent feature: Projecting “further eye,” which extends beyond the outline of the face in profile

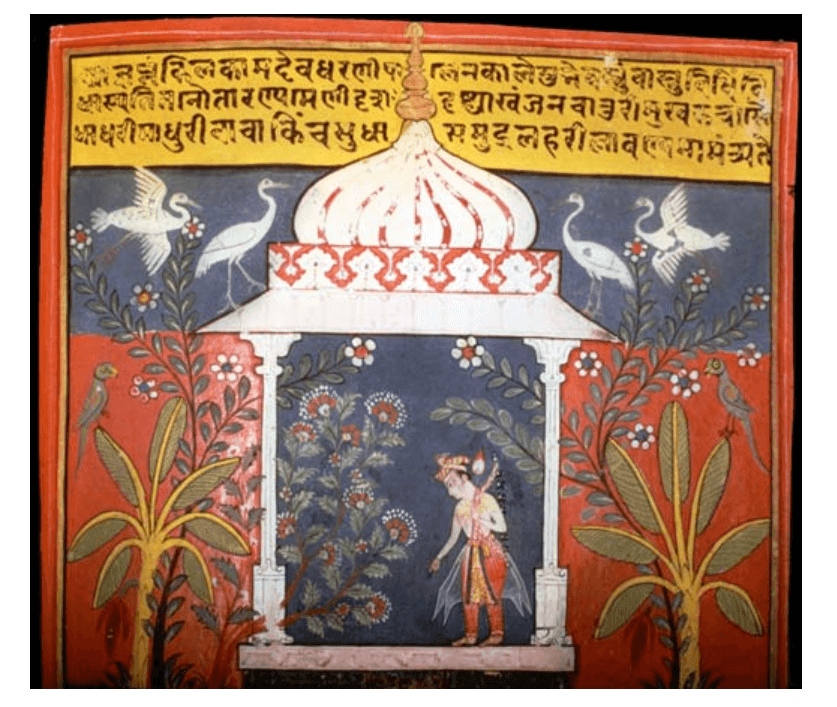

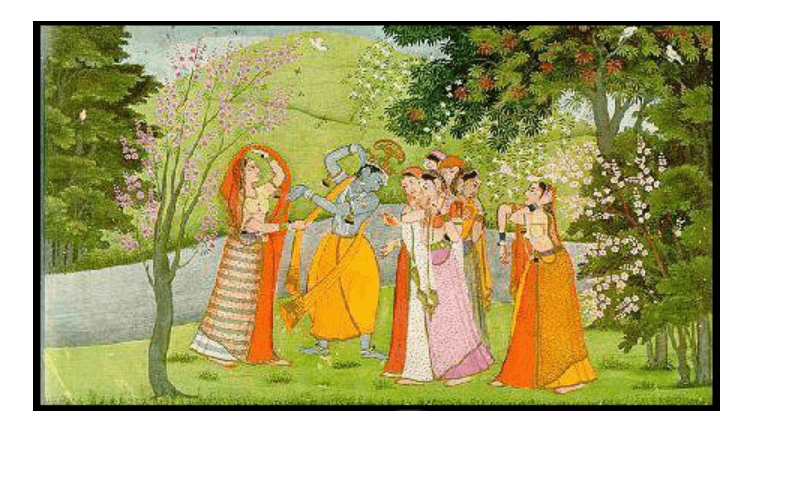

Mughal Paintings (16th – 19th century)

Mainly confined to miniature illustrations on the books or as single works to be kept in an album

Mughal paintings were a unique blend of Indian, Persian (Safavi) and Islamic styles

Marked by supple naturalism: Primarily aristocratic and secular

Tried to paint the classical ragas and Seasons or baramasa

Tutinama – first art work of the Mughal School.

Akbar’s reign (1556–1605) ushered a new era in Indian miniature painting.

At Zenith under Jahangir who himself was a famous painter

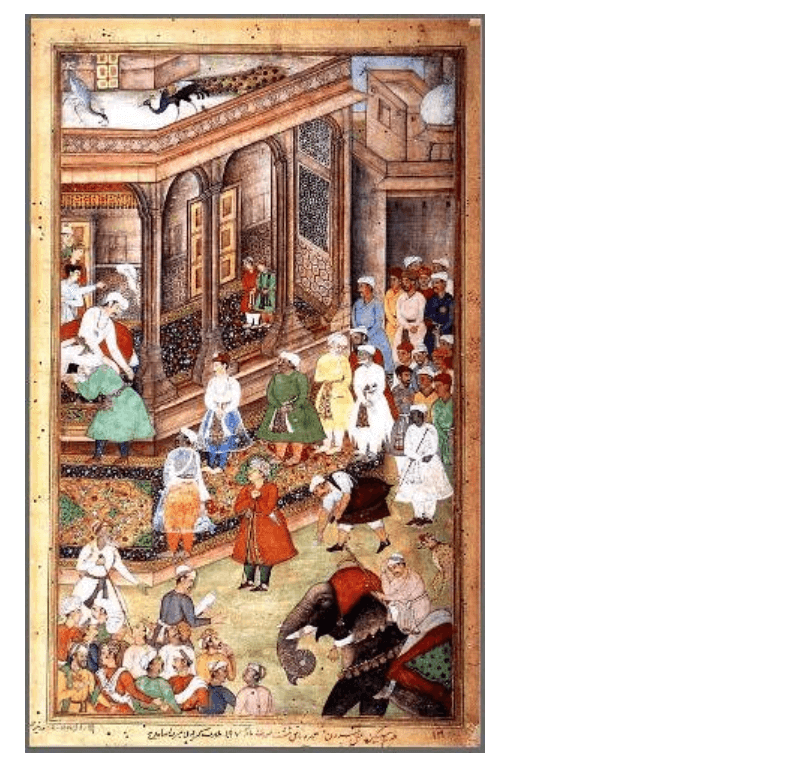

Jahangir encouraged artists to paint portraits and durbar scenes.

Shah Jahan (1627–1658) continued the patronage of painting.

Aurangzeb had no taste for fine arts.

Akbar was the first monarch to establish an atelier in India under the supervision of two Persian master artists, Mir Sayyed Ali & Abdus Samad.

More than a hundred painters were employed, most of whom were Hindus from Gujarat, Gwalior and Kashmir, who gave a birth to a new school of painting, popularly known as the Mughal School of miniature Paintings.

Most significant are Hamza Nama, Razm-Nama or “The Book of War”, Akbar Nama

Finest example of this school includes Hamzanama series, started in 1567 & completed in 1582

Hamzanama : Stories of Amir Hamza, illustrated by Mir Sayyid Ali

1200 paintings on themes of Changeznama, Zafarnama & Ramayana

The paintings of the Hamzanama are of large size, 20” x 27″ and were painted on cloth.

They are in the Persian safavi style with dominating colours being red, blue and green

Indian tones appear in later work, when Indian artists were employed

Rajput Painting (16th – 19th century)

the art of the independent Hindu feudal states in India

Unlike Mughal paintings which were contemporary in style, Rajput paintings were traditional & romantic

Rajput painting is further divided into Rajasthani painting and Pahari painting (art of the Himalayan kingdoms)

Central Indian and Rajasthani Schools (17th – 19th Century)

Deeply rooted in the Indian traditions, taking inspiration from Indian epics, Puranas, love poems & Indian folk-lore

Mughal artists of inferior merit who were no longer required by the Mughal Emperors, migrated to Rajasthan

Rajasthani style prominent features : bold drawing, strong and contrasting colours

Treatment of figures is flat without any attempt to show perspective in a naturalistic manner

Surface of the painting is divided into several compartments of different colours in order to separate one scene from another.

Malwa paintings (17th century)

Centred largely in Malwa and Bundelkhand (MP); sometimes referred as Central Indian painting due to its geographical distribution.

Prominent features : flat compositions, black and chocolate-brown backgrounds, figures shown against a solid colour patch and architecture painted in lively colour.

This school’s most appealing features is its primitive charm & a simple childlike vision.

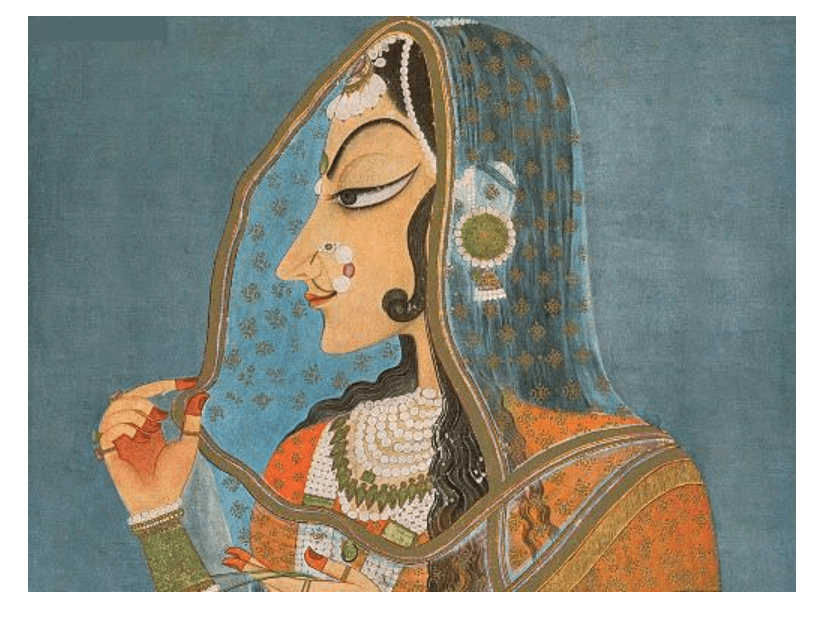

Kishangarh paintings (18th century)

Distinguished by its individualistic facial type and its religious intensity

Developed under the patronage of Raja Savant Singh (1748-1757 AD) by master artist Nihal Chand

Men and women are drawn with pointed noses and chins, deeply curved eyes, and serpentine locks of hair

Their action is frequently shown to occur in large panoramic landscapes

Mewar (Udaipur) Paintings (17th – 18th century)

Characterized by bold bright contrasting colours and direct emotional appeal

The earliest-dated examples come from Ragmala (musical modes) series painted in 1605

Reflects portraiture & life of the ruler, along with religious themes

Text of the painting is written in black on the top against the yellow ground.

Marwar (Jodhpur) Paintings

Executed in a primitive and vigorous folk style

Completely uninfluenced by the Mughal style

Portrays court scenes, series of Ragamala & Baramasa

Bundi paintings (Late 17th century)

Very close to the Mewar style, but the former excels the latter in quality

Prominent features → Rich and glowing colours, the rising sun in golden colour, crimson-red horizon, border in brilliant red colour (in Rasikpriya series)

Notable examples → Bhairavi Ragini (Allahabad Museum), illustrated manuscript of the Bhagawata Purana (Kota Museum) & a series of the Rasikapriya (National Museum, Delhi)

Kota paintings (18th – 19th century)

Very similar to Bundi style of paintings

Themes of tiger and bear hunt were popular

Most of the space in painting is occupied by the hilly jungle

The Pahari Schools (17th – 19th Century)

Comprises the present State of Himachal Pradesh, some adjoining areas of the Punjab, the area of Jammu, & Garhwal in Uttarakhand

Basohli Paintings (17th – 18th century)

Known for its bold vitality of colour, lines & red borders

Emotional scenes from a text called “Rasamanjari” : Krishna legend

Favoured oblong format, with the picture space usually delineated by architectural detail, which often breaks into the characteristic red borders

Stylized facial type, shown in profile, is dominated by the large, intense eyes

Colours are always brilliant, with ochre yellow, brown, and green grounds predominating

Plain monochrome background with facial type became a little heavier& tree forms acquiring somewhat naturalistic character

Depicted jewellery by thick, raised drops of white paint, with particles of green beetles wings to represent emeralds

Guler painting (Jammu)

Mainly consisting of portraits of Raja Balwant Singh of Jasrota (Jammu) designed by Nainsukh

Colours used are soft and cool unlike Basohli school

Style appears to have been inspired by the naturalistic style of the Mughal painting

Kangra painting (Late 18th century)

The Kangra style is developed out of the Guler style & possesses its main characteristics, like the delicacy of drawing & naturalism

The Kangra style continued to flourish at various places namely Kangra, GuIer, Basohli, Chamba, Jammu, Nurpur and Garhwal etc.

However, Named as Kangra style as they are identical in style to the portraits of Raja Sansar Chand of Kangra

In these paintings, the faces of women in profile have the nose almost in line with the forehead, the eyes are long & narrow, & chin is sharp.

There is, however, no modelling of figures and hair is treated as a flat mass.

Paintings of the Kangra style are attributed mainly to the Nainsukh family.

Kullu – Mandi painting

A folk style of painting in the Kulu-Mandi area, mainly inspired by the local tradition

The style is marked by bold drawing and the use of dark and dull colours

Independent Paintings

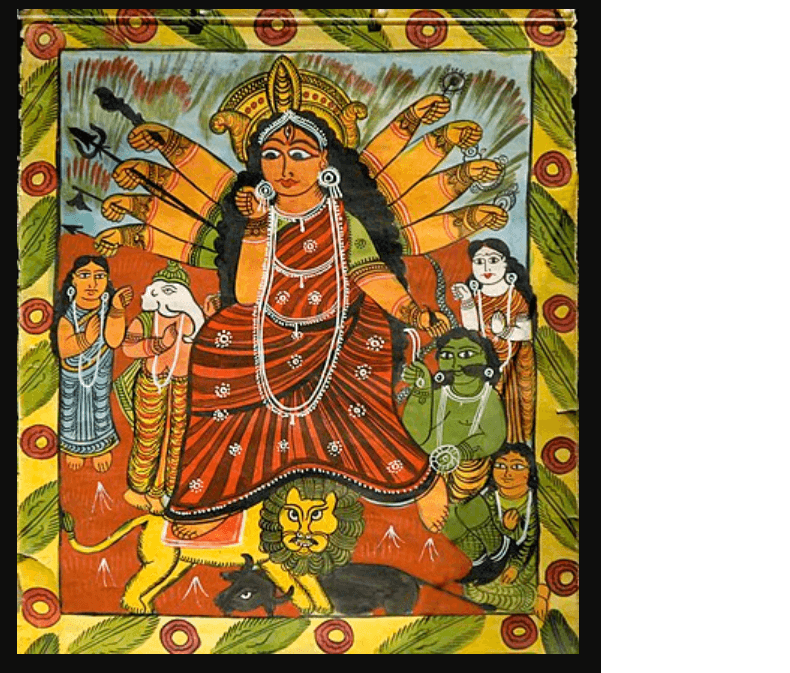

Kalighat Paintings (Kolkata – 19th century)

Patua painters from rural Bengal came and settled in Kalighat to make images of gods and goddesses in the early 19th century

They evolved a quick method of painting on mill-made paper

Used brush and ink from the lampblack

Depicts figures of deities, gentry & ordinary people

Reflects romantic depictions of women

Kalighat paintings are often referred to as the first works of art that came from Bengal

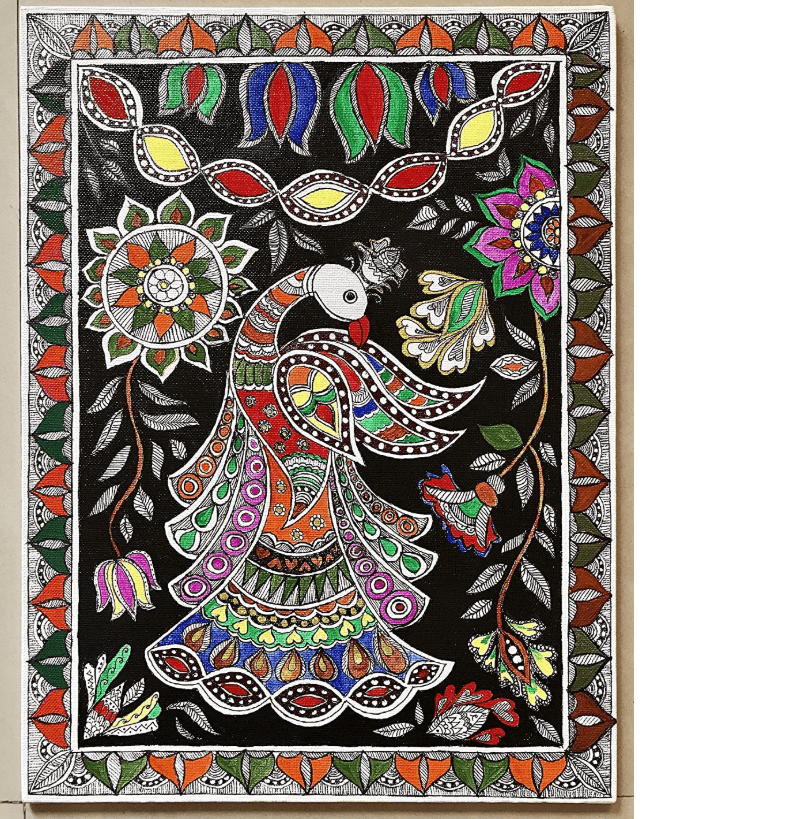

Madhubani Paintings (Mithila, Bihar)

Colourful auspicious images on the interior walls of homes on the occasion of rituals & festivity – painted by women

This ancient tradition, especially elaborated for marriages, continues today.

Used to paint the walls of room, known as KOHBAR GHAR in which the newly wedded couple meets for the first time

Very conceptual, first, the painter thinks & then “draws her thought”

Has five distinctive styles – Bharni, Katchni, Tantrik, Godna and Gobar

Bharni, Kachni and Tantrik style were mainly done Brahman & Kayashth women, who are upper caste women in India and Nepal

Godna & Gobar style is done by the Dalit & Dushadh communities

Phad paintings (Bhilwada, Rajasthan)

Phad is a painted scroll, which depicts stories of epic dimensions about local deities and legendary heroes.

Bhopas (local priests) carry these scrolls on their shoulders from village to village for a performance.

Represents the moving shrine of the deity and is an object of worship.

Most popular & largest Phad – local deities Devnarayanji and Pabuji.

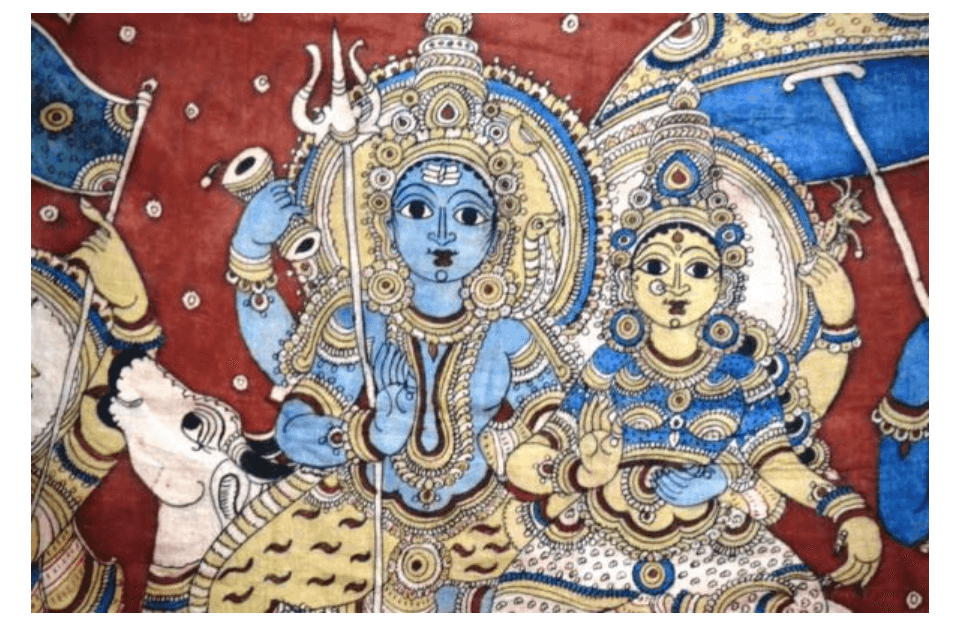

Kalamkari Paintings (Andhra Pradesh)

Literal meaning is painting done by kalam (pen)

Mainly in Andhra Pradesh (developed under Vijaynagar rulers)

Stories from the epics Ramayana, Mahabharata and the Puranas are painted as continuous narratives

Mainly to decorate temple interiors with painted cloth panels scene after scene; Every scene is surrounded by floral decorative patterns

The artists use a bamboo or date palm stick pointed at one end with a bundle of fine hair attached to the other end to serve as brush or pen.

Relevant Telugu verses explaining the theme are also carried below the artwork.

Cloths are painted with the colours obtained from vegetable and mineral sources.

Gods are painted blue, the demons and evil characters in red and green.

Yellow is used for female figures and ornaments.

Red is mostly used as a background

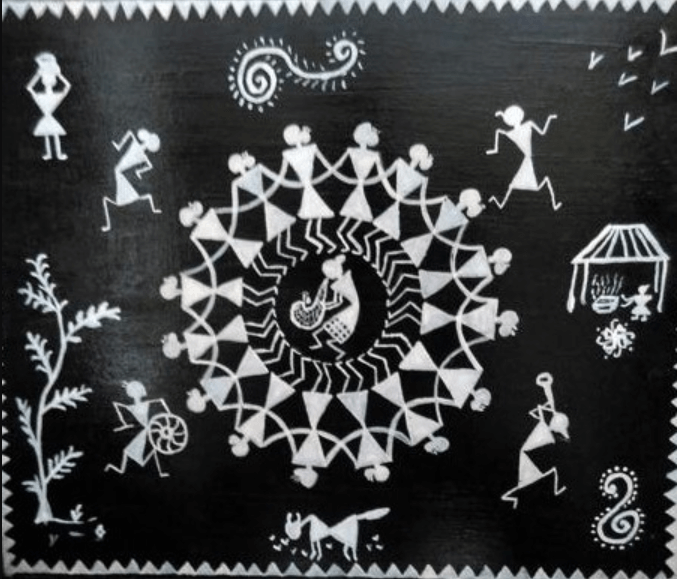

Warli painting

Practiced in tribal regions of Maharashtra with subjects, predominantly religious

decorative paintings on floors & walls of ‘gond’ and ‘kol’ tribes homes and places of worship

made in a geometric patterns like squares, triangles, and circles

Unlike other tribal art forms, Warli paintings do not employ religious iconography and is a more secular art form.

Thangka, Sikkim

Cotton canvas as the base

Influence of Buddhism

Use of different colours for different scenes

Manjusha, Bihar

Also known as Snake painting (use of snake motifs)

Paintings executed on jute and paper

Decorative Art

On walls of homes viz. Rangoli or decorative designs on floor mainly on auspicious occasions

Usually rice powder is used for these paintings but colored powder or flower petals are also used to make them more colorful.

Different Names of Decorative Art

Rangoli North India

Alpana Bengal

Aipan Uttarakhand

Mandana Madhya Pradesh

Rangavalli Karnataka

Kollam Tamilnadu

Kolam

A ritualistic design drawn at the threshold of households and temples.

Drawn everyday at dawn and dusk by women in South India

Kolam marks festivals, seasons and important events in a woman’s life such as birth, first menstruation and marriage.

Kolam is a free-hand drawing with symmetrical and neat geometrical patterns.

Gond Art

Produced by the Santhals in India

Mainly found in Gond tribe of the Godavari belt

Highly sophisticated and abstract form of Art works

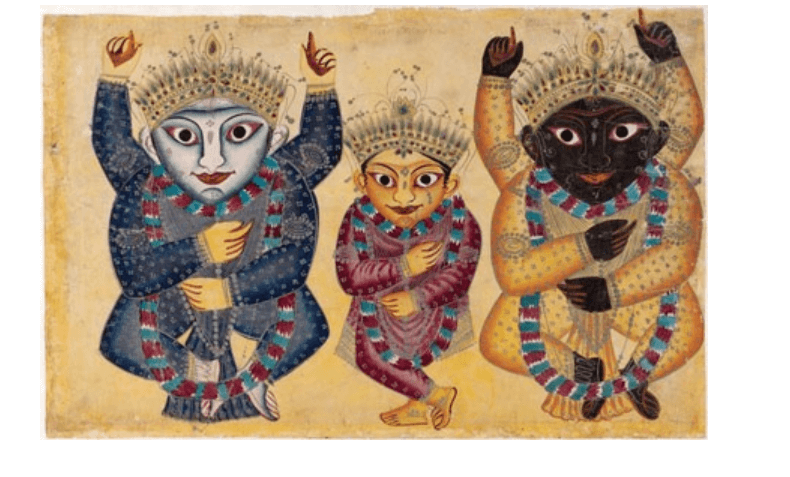

Patachitra (Orissa)

Mostly painted on cloth

Depict stories of Lord Jagannath